Type: Text-based strategic management game

Innovations: First tie-in in history

Key Figures: Mike Mayfield (creator), Bob Leedom (author of Super Star Trek)

Original Version: 1971 (Mainframe version)

Reissues: 1972 (HP 2000C Version), 1974 (expanded conversion), 1984 (Spectrum)

Origin: Computer laboratory of the University of California, Irvine, U.S.A.

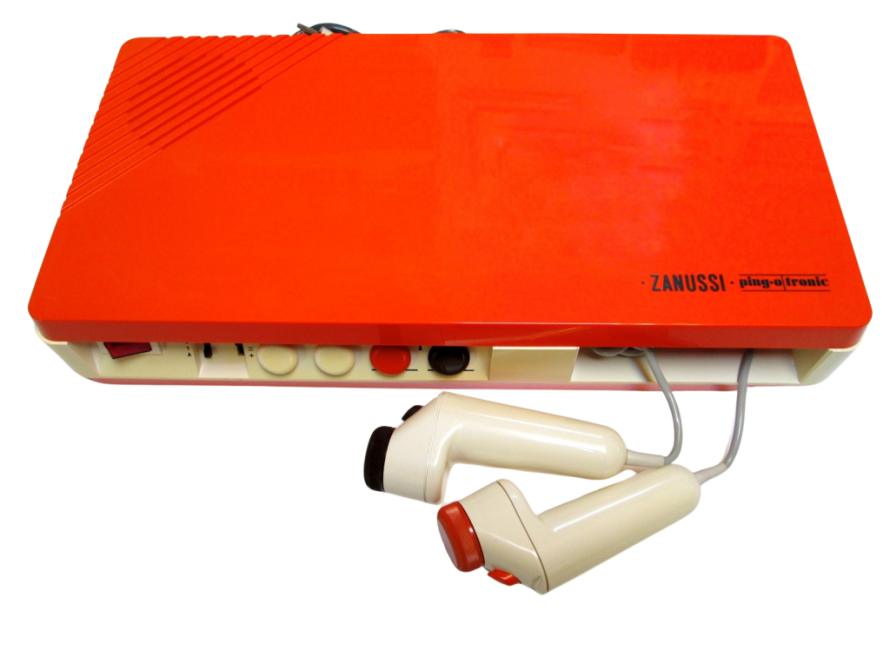

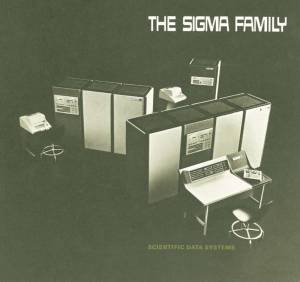

Original System: SDS Sigma 7 Mainframe

Physical Support: Punched Tape

While, in the real world, mass computing was just taking its first steps in the early seventies—gradually moving from large institutions to small offices and eventually private homes—science fiction had already offered a glimpse, albeit romanticized by visionary writers, of what the future of computers would become. A future that, in many ways, we are already living. Today we navigate an age of increasingly powerful computers, capable of genuine graphical miracles, and advanced AIs that can think almost on par with the human brain. Yet back then, all of this belonged solely to imagination. Sci-Fi, more than any other genre, has given us for decades a window into tomorrow, often anticipating not only short- and long-term developments like robots and quasi-self-aware processors, but above all inspiring inventors and engineers to create the devices we now use daily. The communicator from the original Star Trek series, after all, is nothing more than the “modern” mobile phone, which, in the seventies, was beginning to emerge thanks to historic companies like Motorola.

Video games, of course, followed the same evolution, transforming science fiction from screens big and small into electronic entertainment. Today we’re talking about Star Trek, the first text-based strategic video game derived from the TV series, born in 1971 from the mind of Mike Mayfield.

When the Enterprise lived inside terminals: the first Star Trek text game

It’s 1971. While the music world is discovering the psychedelic rock of progressive groups like Pink Floyd, and mainframe computers still occupy entire rooms in dusty American universities, a young programmer—Mike Mayfield, a high-school senior already attending a university lab at UC Irvine—decides to boldly go where no one has gone before. The mission is ambitious: bring the visual grandeur of Star Trek to terminals with no graphics whatsoever—specifically the ASR Teletype Model 33—connected via local network.

Though designed on an SDS Sigma 7 mainframe and developed over more than a year of work, the game soon found a more accessible home: the sturdy yet spartan HP 2000C minicomputer, which today would likely pale next to a modern smartphone. This system was provided by HP’s commercial division. Thus was born the first text-based strategy videogame dedicated to the saga, a space journey made only of letters, numbers, and a whole lot of imagination. But that, ultimately, is the core of what a “videogame” is—a term coined, as we know, by Steve Russell for Spacewar!

Despite the total absence of visual effects, the game managed—thanks to its charisma and narrative tension—to captivate generations of students and programmers starting in the seventies, evolving as real-world computers advanced. The game’s galaxy is represented as a simple 8×8 grid of quadrants—64 total—true to the fictional universe created by Gene Roddenberry. Each quadrant contains another 8×8 grid of sectors. A layout so geometric and perfect that even Spock would have found it “statistically elegant.”

The player assumes the role of captain aboard the legendary USS Enterprise, armed with phasers, photon torpedoes, and an energy reserve that depletes faster than Captain Kirk’s patience during a diplomatic negotiation. Every command is entered through the classic text parser, making the game immediately accessible.

A squadron of Klingon warbirds—made only of numbers and letters—threatens humanity!

The objective of Mayfield’s game is simple and consistent with the show, especially the wartime moments against the Federation’s historic enemies. The player must eliminate a number of Klingon ships scattered across the galaxy before the assigned stardate expires. A straightforward mission which, through its purely text-based presentation, becomes an interactive narrative as gripping as a novel—only this time, the actions are decided by a human player sitting at a terminal. A dream come true for kids of the era!

The first American college “nerds,” many already on scientific study paths, were often inspired by the legendary TV series. Alongside the game grid, the interface displays the ship’s Conditions as well as Torpedoes, Energy, Shields, and Klingons—showing exact values for each element. At the bottom of the screen, the Command interface awaits your captain’s orders.

Nothing too complex for those used to academic computers and terminals—except for one detail: Klingon ships hate diplomacy. They prefer to fire on sight at Starfleet, the historic enemies of the inhabitants of Kronos (Qo’noS), the Klingon homeworld. With an always-hostile empire, the player must act fast: Enterprise systems are fragile under Klingon fire, and get damaged as easily as Scotty yelling, “I cannae change the laws of physics!” with his iconic Scottish accent.

The original TV series, meanwhile, anticipated the modern notion of “inclusion” by placing Americans, Russians, and Japanese together on the bridge—plus a Vulcan and a Black communications officer, who shared one of the first interracial kisses in television history with the ever-charming Captain Kirk. But let’s not digress like Grandpa Simpson—and return to the game.

A text-based strategic videogame to explore deep space

The gameplay of Mayfield’s Star Trek is mathematically precise—a tactical dance conducted entirely through text commands. A game of another era, sure, but with a charm that remains intact more than fifty years later. Memorizing commands is crucial: three-letter uppercase strings trigger every action. NAV moves the ship, PHA fires phasers, TOR launches photon torpedoes, SRS and LRS activate short- and long-range sensors, and SHE raises the shields—vital for survival. Without shields, the Enterprise lasts about three turns. Losing them means a swift, hopeless GAME OVER.

The game uses alternating turns—player and enemy—like an intense (Vulcan) chess match. Starbases located throughout the quadrants can recharge consumables. Every action is narrated with cold, concise Teletype terminal language—no epic soundtrack, no bridge explosions—just lines like “Klingon at sector 5,3 attacks for 200 units.” Despite their dryness, these messages send chills down players’ spines. A minimal prose that would please the android Data (who wouldn’t appear in the franchise until 1987), though likely less appreciated by the fiery Dr. McCoy: “I’m a doctor, not a robot!” he might have shouted.

Each game differs thanks to advanced algorithms devised by Mayfield. Replayability is extremely high, which quickly drove its success across university campuses.

The evolution of Star Trek and its later versions

Star Trek was compiled in 1971 by Mike Mayfield on an SDS Sigma 7 mainframe in a programming language, but it was soon entirely rewritten in HP Time-Shared BASIC in 1972 on an HP 2000C minicomputer so it could run on simpler devices. A fully text-based game, designed for BASIC and played via Teletype terminals—simple printing consoles without graphics. Initially the game spread manually, with source code copied by hand. Hewlett-Packard believed in the project so much that it included the game as standard software in its official library. This gave it tremendous visibility and lasting success, along with reissues that added new features over time.

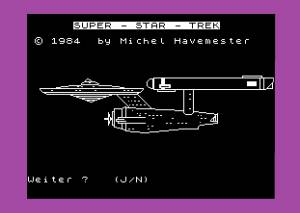

In 1973, David H. Ahl and Mary Cole recompiled the game in BASIC PLUS for industry publications, making it compatible with DEC systems. The edition that brought the most fame, however, was Super Star Trek, an expanded 1974 version by Bob Leedom—later used as the foundation for many subsequent releases. David Matuszek and Paul Reynolds later converted the game into Fortran, and versions eventually appeared on Unix, DOS, and Windows. The famous EGA Trek for IBM PC even added new graphical screens. Over time, the game multiplied like tribbles during mating season: Apple Trek by Wendell Sander arrived on Apple systems in 1979; even consoles like the Atari VCS hosted variants (under different names due to licensing). Voice support emerged with TI-Trek for the TI-99/4A in 1983, which used the system’s speech synthesizer, and Michel Avemester produced the 1984 Spectrum version with static Enterprise images.

Alongside commercial editions, many versions based on Mayfield’s original code appeared, and today the internet still hosts online adaptations.

Over the years, version after version, the text-based Star Trek videogame exploded in popularity, becoming a cult classic—present in countless variations on American computers. What began as a student project evolved into one of the most widespread titles of the seventies, a true cornerstone of gaming history. It is also the first tie-in (a game based on a film or TV series) ever made.

Looking back with historical perspective, the game has an irresistible retro charm—a space mission with no graphics, capable of evoking interstellar battles using only text. Long before 3D engines—or even 8-bit graphics—a little imagination and a noisy terminal were enough to feel like you were commanding the bridge. A simple, brilliant, and surprisingly engaging experience—proof that you don’t need to bend space-time to make a great game. Sometimes, all it takes is a bit of BASIC and the desire to go where no programmer has gone before.

Author:

Fabio D’Anna

Stay updated on GAMM news and events. Visit News – GAMM Game Museum!